Leitgeb's First Name

Why this musician is still adorned with the name "Ignaz" in New Grove (albeit in brackets), is an absolute mystery. In 1970, the German Kapellmeister Karl Maria Pisarowitz began his article "Mozarts Schnorrer Leutgeb. Dessen Primärbiographie" (Mitteilungen der ISM, VIII [1970], vol. 3/4, 21–26) with the following trademark exclamation:

Nein! Jedenfalls hieß er niemals "Ignaz", dieser attraktiv gottbegnadete Waldhornvirtuose, der als "Ignaz Leutgeb (Leitgeb)" irtümlicherweise in die bislange Mozart-Publizistik lebensdatenlos eingehen mußte!

No! In no case was his name ever "Ignaz", this attractively and divinely gifted virtuoso of the natural horn, who had to enter the Mozart literature by mistake as "Ignaz Leutgeb (Leitgeb)" and without biographical dates.

Leitgeb appearing with a wrong first name and a wrong date of birth in the list drawn up by the society's secretary Stephan Franz (A-Wsa, Private Institutionen, Haydn-Verein, A1/2, Sonderakten)

Pohl's failure to actually read the society's minutes led to numerous false birth dates of musicians that still haunt the modern literature (and encyclopedia articles like the one about Johann Nepomuk Went in the ÖML). In the case of Leitgeb, Stephan Franz's errors duly reappear in Pohl's book.

The names "Leutgeb" and "Leitgeb" bear no onomastic difference and are completely exchangeable. I prefer to use the second spelling, because that is how Leitgeb himself signed his family name.

Leitgeb's Date of Birth

The actual records of the Tonkünstler-Societät show that Franz also got Leitgeb's date of birth wrong. Joseph Leitgeb was born on 6 October 1732, two days earlier than the date given in Stephan Franz's list. When on 30 October 1787 Leitgeb applied for membership in the society, he had to submit his birth certificate (a procedure Mozart never managed to follow through). Leitgeb's second wedding had already taken place on 15 January 1786, but his employment in Preßburg had delayed his application which was recorded in the minutes of the society as follows (A-Wsa, Private Institutionen, Haydn-Verein, A2/1).

25.Leutgeb Joseph (geb: den 6ten 8ber 732) / Waldhornist beÿ (Tit[ulo]) Herrn Fürsten v / Krassalkowitz suchet an in die Societät / aufgenommen zu werden.

Fiat, und kann der Supplicant gegen Erlag / der Stattutenmässigen Schuldig- / keiten auf den 16ten 9ber a:[nni] c:[urrentis] in die / Societät eintretten. Exped[itum] d[en] 5tn 9br a: c:

Leutgeb Joseph (born 6 October 1732) hornist with Count von Grassalkovics applies for membership in the society.

So be it. The supplicant is allowed to join the society on 16 November of this year after the payment of the statutory fees

Pisarowitz did all his pioneering research by mail from his home in Bavaria and never went to Salzburg and Vienna to personally check the sources and verify Pohl's data. As far as archival sources were concerned, he only relied on the flawed and fragmentary information that he received from Heinz Schöny, Rudolf Hackel and Gerhard Croll. Regarding the church records pertaining to Joseph Leitgeb's birth, Pisarowitz in 1970 was told by the Neulerchenfeld parish in Vienna that their 1732 baptismal register "was destroyed in the war in 1945". This was the universally accepted state of knowledge, until on 8 October 2009 (Leitgeb's supposed 177th birthday), when I visited the Neulerchenfeld parish office and its adorable secretary. She did not really know how far back the surviving church records went and suggested that the earliest books cover the years right after the 1783 parish reform of Joseph II. "What is that small book up there, on top of all the others?" I asked her. And there it was, the supposedly lost parish register, covering (as was the common procedure in eighteenth-century country villages) all the marriages, baptisms and burials from 1721 until 1741 in one small, unpaginated and unindexed volume.

Here is Joseph Leitgeb's never before published baptismal entry (Pfarre Neulerchenfeld, Tom.1).

It is to be noted that at that time Neulerchenfeld was not located in Vienna, but in Lower Austria. In 1749, the parish priest issued Joseph Leitgeb's baptismal certificate of which (for still unknown reasons) a copy was made in 1806. I came across this seemingly misplaced document in an 1806 divorce file that has no provable relation to Joseph Leitgeb.

Joseph Leitgeb's father Leopold was not just a violinist. Just like Joseph Stadler (1719–1771), the father of the clarinet players Anton and Johann Stadler, who, a shoemaker by profession, for a certain time of his life, also worked as a musician, Leopold Leitgeb changed his breadwinning according to the demand, and in 1740 and 1742, he is referred to in the records as "Tagwerker" (day laborer) and "Eisentandler" (ironmonger).

It goes without saying that Joseph Leitgeb learned to play the violin from his father. The information given by Werner Rainer in his 1965 biographical article on Adlgasser that "from 1763 on Leitgeb was employed by the Salzburg court as violinist" does not need "to be corrected" (as Pisarowitz claimed in 1970), because it is based on historical facts. Like every other wind player of the Salzburg court chapel, Leitgeb was also a proficient violinist who regularly performed on this instrument in case no horn player was needed. His father Leopold seems to have been the "widowed musician Leopold Leitgeb" who died on 4 June 1789, at the age of 93, in the "Langenkeller" (today Burggasse 69), a Viennese poorhouse. Owing to the lack of probate records, however, the family relationship of this Leopold Leitgeb to the horn player remains yet to be proved.

In 1752, Leitgeb's brother Johann – also a musician – got married in Neulerchenfeld to Theresia Kolmb, daughter of Mathias Kolmb, a "Parchenmacher" (maker of cotton flannel).

In 1760, Leitgeb's younger sister Katharina married Anton Nasel, a locksmith from Ostritz in Saxony.

Joseph Haydn's supposed Godparenthood of Leitgeb's First Child

On 2 November 1760, in the church of St. Ulrich in Vienna, Joseph Leitgeb married Barbara Plazzeriani (Placereani), a cheesemaker's daughter from Altlerchenfeld.

According to Pisarowitz, the couple was already pressed for time, because "the bride was already pregnant and either in 1760, or early 1761, gave birth to her first child 'Ernst Leüthgeb' who had evidently been fathered premaritally" ("deren evident vorehelich gezeugter Erstsproß"). This is false. It is no surprise that Pisarowitz's Viennese assistant (probably the genealogist Heinz Schöny) could not find the baptismal entry of this alleged first child in a Viennese parish register. Ernst Joseph Leitgeb (named after his godfather Ernst Maximilian Köllenberger, the controller with the Salzburg Obersthofmarschallstab) was born in Salzburg only on 30 October 1766.

Ernst Leitgeb became a watchmaker, had three sons with his wife Juliana, née Haberreiter in Alt- and Neulerchenfeld, and died at a relatively young age. In 1820, his second son Ernest (16 July 1794 – 2 July 1836) was a valet of Ignaz Sonnleithner and after Sonnleithner's death in 1831, worked as a clerk with the Erste österreichische Spar-Casse. One of his sons, Ernst Leitgeb, is documented to have still been alive in 1892.

Between 27 November 1761, and 28 January 1763, Joseph Leitgeb appeared playing horn concertos at the Burgtheater no fewer than fourteen times. According to the chronicle of the dancer Philipp Tobias Gumpenhuber (1708–1770), on 2 July 1762, Leitgeb performed a horn concerto by Michael Haydn which is unfortunately lost (as are two other concertos played by Leitgeb by composers such as Leopold Hofmann and Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf).

On the following day, on Saturday, 3 July 1762, Leitgeb's first child Anna Maria Catharina was baptized at St. Ulrich's.

The title page of the supposedly lost 1721-42 register (Tom. 1) of the Neulerchenfeld parish

Here is Joseph Leitgeb's never before published baptismal entry (Pfarre Neulerchenfeld, Tom.1).

den 6 [October 1732] Joseph: P:[ater] Leopold Leütgeb Geiger Rosina Ux[or] Gevatt[er] / Joseph Kornberger Würth.

On October 6th, [the child] Joseph [father] Leopold Leutgeb violinist Rosina [his wife] godfather Joseph Kornberger, an innkeeper.

A copy of Joseph Leitgeb's 1749 baptismal certificate which, for unknown reasons, was drawn up in 1806 (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A6, 14/1806).

Joseph Leitgeb's father Leopold was not just a violinist. Just like Joseph Stadler (1719–1771), the father of the clarinet players Anton and Johann Stadler, who, a shoemaker by profession, for a certain time of his life, also worked as a musician, Leopold Leitgeb changed his breadwinning according to the demand, and in 1740 and 1742, he is referred to in the records as "Tagwerker" (day laborer) and "Eisentandler" (ironmonger).

Leopold Leitgeb given as "Leopold Leüthgeb eisentändler", as godfather of the day laborer's son Leopold Augustin Hochenetzer on 27 August 1742 (Pfarre Neulerchenfeld, Tom. 1)

It goes without saying that Joseph Leitgeb learned to play the violin from his father. The information given by Werner Rainer in his 1965 biographical article on Adlgasser that "from 1763 on Leitgeb was employed by the Salzburg court as violinist" does not need "to be corrected" (as Pisarowitz claimed in 1970), because it is based on historical facts. Like every other wind player of the Salzburg court chapel, Leitgeb was also a proficient violinist who regularly performed on this instrument in case no horn player was needed. His father Leopold seems to have been the "widowed musician Leopold Leitgeb" who died on 4 June 1789, at the age of 93, in the "Langenkeller" (today Burggasse 69), a Viennese poorhouse. Owing to the lack of probate records, however, the family relationship of this Leopold Leitgeb to the horn player remains yet to be proved.

In 1752, Leitgeb's brother Johann – also a musician – got married in Neulerchenfeld to Theresia Kolmb, daughter of Mathias Kolmb, a "Parchenmacher" (maker of cotton flannel).

The entry concerning the wedding of the Musicus Johann Leitgeb and Theresia Kolmb on 31 Januar 1752. The groom's father is also addressed as "Musicus" (Pfarre Neulerchenfeld, Tom. 1, pag. 56).

In 1760, Leitgeb's younger sister Katharina married Anton Nasel, a locksmith from Ostritz in Saxony.

The entry concerning the wedding of Anton Nasel and Katharina Leitgeb on 19 February 1760. The bride's father Leopold Leitgeb is addressed as "Geiger" (violinist) and referred to as living in the house "Zum Goldenen Schlössel" ("At the Golden Castle", today Gaullachergasse 23). (Pfarre Neulerchenfeld, Tom. 1, pag. 99)

Joseph Haydn's supposed Godparenthood of Leitgeb's First Child

On 2 November 1760, in the church of St. Ulrich in Vienna, Joseph Leitgeb married Barbara Plazzeriani (Placereani), a cheesemaker's daughter from Altlerchenfeld.

A certificate, issued on 1 November 1760 by the Neulerchenfeld parish priest Franz Anton Appeller, concerning the three unchallenged publications of the banns in the Joseph Leutgeb's home parish and his and his bride's religious examination (A-Wsa, Konfessionelle Behörden, St. Ulrich, A2/3)

The entry concerning the wedding of Joseph Leitgeb and Barbara Plazzeriani on 2 November 1760, at St. Ulrich's Church (St. Ulrich, Tom. 24, fol. 154v). A flawed and incomplete transcription of this document was published in 1970 by Pisarowitz.

According to Pisarowitz, the couple was already pressed for time, because "the bride was already pregnant and either in 1760, or early 1761, gave birth to her first child 'Ernst Leüthgeb' who had evidently been fathered premaritally" ("deren evident vorehelich gezeugter Erstsproß"). This is false. It is no surprise that Pisarowitz's Viennese assistant (probably the genealogist Heinz Schöny) could not find the baptismal entry of this alleged first child in a Viennese parish register. Ernst Joseph Leitgeb (named after his godfather Ernst Maximilian Köllenberger, the controller with the Salzburg Obersthofmarschallstab) was born in Salzburg only on 30 October 1766.

The

entry concerning the baptism of Ernst Joseph Leitgeb on 30 October 1766

in the Salzburg Cathedral (Archiv der Erzdiözese Salzburg, Dompfarre

9/2, 219)

Ernst Leitgeb became a watchmaker, had three sons with his wife Juliana, née Haberreiter in Alt- and Neulerchenfeld, and died at a relatively young age. In 1820, his second son Ernest (16 July 1794 – 2 July 1836) was a valet of Ignaz Sonnleithner and after Sonnleithner's death in 1831, worked as a clerk with the Erste österreichische Spar-Casse. One of his sons, Ernst Leitgeb, is documented to have still been alive in 1892.

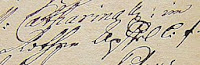

The signature of Joseph Leitgeb's grandson Ernest Leutgeb (1794–1836), "Kassediener bey der allgemeinen Versorgungsanstalt" (A-Wstm, SP Rapular 1818-34)

Between 27 November 1761, and 28 January 1763, Joseph Leitgeb appeared playing horn concertos at the Burgtheater no fewer than fourteen times. According to the chronicle of the dancer Philipp Tobias Gumpenhuber (1708–1770), on 2 July 1762, Leitgeb performed a horn concerto by Michael Haydn which is unfortunately lost (as are two other concertos played by Leitgeb by composers such as Leopold Hofmann and Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf).

The entry in Gumpenhuber's Répertoire concerning Leitgeb's concert at the Burgtheater on 2 July 1762 (A-Wn, Mus.Hs. 34580/b, 68f.)

On the following day, on Saturday, 3 July 1762, Leitgeb's first child Anna Maria Catharina was baptized at St. Ulrich's.

The 1762 baptismal entry of Anna Maria Leitgeb. Note that there is always an idiot with a ballpen (St. Ulrich, Tom. 30, fol. 314v)

den 3:tenP:[ater] Josephus Leüthgeb, ein / Musicus, in der golden Aull allhier. / M.[ater] Barbara Ux:[or] / Inf:[ans] Anna M[a]r[i]a Catharina / M[atrina]: Fr:[au] M[a]r[i]a Anna Haÿdenin / mar:[itus] H[err] Joseph, Capell M[ei]ster / von Fürst Esterhasÿ, abs:[ens] / R:[everendus] P:[ater] Gerardus / Obst:[etrix] Kammerlingin

The text of this entry has been published twice: first, by Pisarowitz in 1970, and second, by Ingrid Fuchs in 2009, in the commentary of the facsimile edition of Haydn's horn concerto in D major Hob. VIId:3. Pisarowitz led Daniel Heartz to believe that both Joseph Haydn and his wife actually officiated as godparents at the baptism of Leitgeb's first child. Ingrid Fuchs, relying on a new (but flawed) transcription by Hubert Reiterer, misunderstood it in a similar way and also presented Haydn as godfather of this child. This presumption is false. Only Haydn's wife officiated as Anna Maria Leitgeb's godparent. The key to the understanding of this entry does not lie in the text itself, but in general knowledge of eighteenth-century baptismal entries and their sometimes not too obvious meaning. Joseph Haydn was not the godfather for the following reasons: 1) Haydn's name is given only as the attribute of his wife's social status. According to the social rules valid at that time she was nobody except for being the wife of "Count Esterházy's capellmeister". This is also corroborated by the absence of the essential word "et" (and) between hers and her husband's name. The St. Ulrich baptismal records show that the abbreviation "mar:" does not mean "marita" (wife), but "maritus" (husband) which refers to the godmother's husband whose name and position signifies her social status. This can be nicely demonstrated with the 1732 baptismal entry of Leitgeb's first wife.

2) The overwhelming majority of girls in eighteenth-century Vienna had godmothers. 3) If Haydn had been joint godparent he would of course have been listed first and his wife would have been reduced to "Maria Anna ux:". Never would his name have appeared after his wife under the plural attribute "Matrini" (godparents). 4) The addition "absens" (turned into the nonsensical "absentibus" by Pisarowitz) was obviously added to indicate that the husband was not the godfather, and finally e) had the Esterházy capellmeister actually been the godfather, one of the child's three names would most likely have been Josepha. Anna Maria Leitgeb already died on 24 October 1763, of chickenpox (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 57, L, fol. 27v).

The entry concerning the baptism of Maria Barbara Plazeriano on 20 November 1732, at St. Ulrich's. Note that the chimney sweep Christoph Imini was not a godparent and is only given as "Maritus" of the godmother, his wife Barbara Imini. The "aplisches hauß" in Altlerchenfeld belonged to a relative of Leitgeb's second wife. (St. Ulrich, Tom. 21, fol. 209r). A flawed transcription of this entry was published in 1970 by Pisarowitz.

2) The overwhelming majority of girls in eighteenth-century Vienna had godmothers. 3) If Haydn had been joint godparent he would of course have been listed first and his wife would have been reduced to "Maria Anna ux:". Never would his name have appeared after his wife under the plural attribute "Matrini" (godparents). 4) The addition "absens" (turned into the nonsensical "absentibus" by Pisarowitz) was obviously added to indicate that the husband was not the godfather, and finally e) had the Esterházy capellmeister actually been the godfather, one of the child's three names would most likely have been Josepha. Anna Maria Leitgeb already died on 24 October 1763, of chickenpox (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 57, L, fol. 27v).

The entry concerning Anna Leitgeb's burial in the St. Ulrich cemetery on 26 October 1763. The burial expenses amounted to 1 gulden 30 kreuzer. "d: P:" means "dem Pfarrer", "kl: gl:" means "kleines gleuth" (St. Ulrich, Tom. 20, 726).

Joseph Leitgeb's earliest documented residence in Vienna: the house St. Ulrich No. 9, "Zur goldenen Eule" ("At the Golden Owl", today Neustiftgasse 18) opposite the church of St. Ulrich.

The Ferber-Starzer-Connection

Anna Maria Catharina was of course not the last Leitgeb child with an interesting godmother. On 28 October 1771, Rosina Starzer served as godmother to Leitgeb's daughter Rosina. Not only was Rosina Starzer the sister of the composer Joseph Starzer (1728–1787), she was also the daughter of the horn player Thomas Starzer (b. 14 November 1699 in Niederaltaich [Niederaltaich, Tom. 1, 220], d. 17 April 1769, Vienna), who may well have been Leitgeb's horn teacher. Rosina Starzer herself was the goddaughter of Rosina Ferber (A-Wd, Tom. 69, fol. 224v), wife of the horn maker Adam Ferber (1700–1749).

The entry concerning Rosina Leitgeb's baptism on 28 October 1771 with "Rosina Starzerin Kay[serliche] Trabantens=Tochter l.[edigen] St.[ands]" serving as godmother (St. Ulrich, Tom. 33, fol. 276v)

The seal and handwriting of Rosina Leitgeb's godmother Rosina Ulbrich, née Starzer (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 9/1790)

The Myth of Leitgeb's Cheese Shop

That "the horn player Leutgeb was a cheesemonger in a suburb of Vienna" is a popular myth that persistently refuses to die ("Blessed are the cheese-makers, for they shall have Mozart horn concertos."). This narrative is based on a number of misunderstandings aggravated by lack of archival research. Leitgeb's first father-in-law Biagio Placeriano was born around 1686, in the Friulian village of Montenars (he is related to the Italian author Francesco Placereani). The presence of Placeriano's older brother Antonio (who also was a cheesemaker) in Vienna is documented as early as 1724, on the occasion of his wedding to Theresia Collin on 11 June of that year, in Lichtental (Lichtental, Tom. 1, p. 28). Biagio seems to have accompanied or followed his brother to Vienna where he also worked as "Welischer Käßmacher" (Italian cheesemaker). A "travelling cheesemaker" named Jakob Placeriano (possibly a third brother) died on 29 April 1771, aged 48 years, in Vienna (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 65, BP, fol. 25r). On 3 February 1732, Biagio married Catharina Morelli, the daughter of his landlord in Altlerchenfeld, the bellows maker Nicolaus Morelli (St. Ulrich, Tom 17, fol. 159v). In Morelli's house "Zum heiligen Geist", Altlerchenfeld No. 42 (today Lerchenfelderstraße 160, a building torn down in 1881) Placeriani established a shop where he produced Italian sausages and hard cheese.

The far outskirts of Altlerchenfeld near Vienna's Linienwall in 1778: on the upper left the house No. 42 where until 1763, Biagio Placeriano's cheese shop was located, on the right No. 32 "Zur Heiligen Dreifaltigkeit", the house Joseph Leitgeb bought in 1777. This little-known Mozart site was destroyed in 1974.

Leitgeb's house "Zur Heiligen Dreifaltigkeit" in 1950 (A-Wsa, Fotosammlung C 7017/2155)

Biagio Placeriano in Vienna's 1748 tax register (A-Wsa, Steueramt B 4/127, fol. 150v)

It is important to note that Placeriano was not a regular cheese maker (a profession classified as "Kässtecher" in eighteenth-century Vienna), but a so-called "Cerveladmacher" (also "Servaladawürstmacher"), which means that he produced various sorts of Italian cured meat sausages (Salumi) and Italian hard cheese, such as Parmesan. On 16 October 1763, Biagio Placeriano died of lung gangrene (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 57, BP, fol. 67v), at a time when his son-in-law was still employed in Salzburg.

Seal and signature of Leitgeb's first father-in-law Biagio Placeriano (1686–1763). The seal bears the initials "B P" (A-Wsa, AZJ, 11676/18. Jhdt.).

The entry concerning Biagio Placeriano's burial on 18 October 1763, in the St. Ulrich cemetery. The abbreviated address reads "in Heiligen Geist lerchen Feld". The relatively high burial expenses of 7 gulden and 52 kreuzer consisted of fees for "dem Pfarrer bezahlt", "Mittleres gleuth", "6 Windlichter", and "X [Kreuz] und Bild". (St. Ulrich, Tom. 20, 723)

For a short time, Placeriano's widow kept the cheese shop going, but in 1764, she sold the "Cerveladmachergerechtigkeit" (the dry sausage making license) to a certain Johann Rotter (misspelled "Rotta" in the records). Her horn playing son-in-law Joseph had nothing to do with all this. Between March 1763 (after his unsuccessful employment at the Esterházy court), and 14 September 1763 (the date of birth of his son Johann Anton), he had moved to Salzburg and joined the chapel of the archbishop. The transfer of the sausage and cheese shop from Placeriano's widow to Rotter in 1764 is documented in the business tax records of the City of Vienna.

The business tax register of Placeriano's sausage and cheese shop in Altlerchenfeld. The two entries on the left read "seine Wittwe" (his widow) and in 1764 "von hier hinweg Johann Rotta" (as of here Johann Rotta). (A-Wsa, Steuerbuch B 8/1, fol. 417r)

Of course, the blame for the origin of the "cheese shop myth" lies with Leitgeb himself. On 1 December 1777, Leopold Mozart wrote the following to his son in Mannheim:

H: Leutgeb, der itzt in einer vorstatt in Wienn ein kleines schneckenhäusl mit einer kässtereÿ gerechtigkeit auf Credit gekauft hat, schrieb an dich und mich, kurz nachdem du abgereiset, und versprach mich zu bezahlen mit gewöhnlicher voraussetzung der Gedult bis er beÿm käs=Handl reicher wird und von dir verlangte er ein Concert.[translation:]

Mr. Leutgeb, who now has bought on credit a snail's shell with rights to a cheese business in a suburb of Vienna, wrote to us after you left and promised to pay me with the usual implication of patience until he will get richer trading cheese and from you he requested a concerto.

Viennese archival records, such as tax registers and the 1788 Steuerfassion, however, show that Leitgeb never ran a cheese shop. Since it is highly unlikely that he had the expertise and the necessary business prospects to actually become a cheesemonger, it seems that this cheesemaking story only served as part of a scheme to elicit money from Leopold Mozart. When in 1777 Leitgeb and his wife bought the house "Zur Heiligen Dreifaltigkeit" ("The Holy Trinity", built in 1748, today Blindengasse 20) at an auction from the furrier Anton Ditzler, they had to borrow the larger part the money from Ferdinand Aumann (1739–1795), a butcher in Penzing.

The entry concerning the official certification on 6 February 1779, of the purchase of the house Altlerchenfeld 32 by Joseph and Barbara Leutgeb (A-Wsa, Patrimonialherrschaften, B146/6, fol. 125r).

On 1 July 1778, Leitgeb already had to mortgage the house at a four percent interest rate. In 1783, the mortgage was transferred to a certain Joseph Aufmuth and was only discharged in 1812, after Leitgeb's death. It is very unlikely that Leopold Mozart was ever paid back the money he had lent his former colleague musician.

Leitgeb and Haydn's Horn Concerto in D, Hob. VIId:3

There has been a long-standing agreement among musicologists that Haydn expressedly wrote his horn concerto for Leitgeb, and his 1762 concert series at the Burgtheater. This reasoning is not only based on Haydn's dating with 1762, but also on a number of other circumstances. In his article about the Haydn horn concertos, Daniel Heartz wrote:

The same year that brought Michael Haydn back to Vienna, that provided Joseph Leutgeb with so many horn concertos, was also, as we have seen, the date of Joseph Haydn's horn concerto in D. The work survives only in Haydn's autograph, dated 1762, and is preserved in the library of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde. If Joseph Haydn would have been as conscientious about precise dating as his brother Michael perhaps he would have inscribed a date close to the baptism of Leutgeb's daughter and the performance of the concerto by "Michel Hayde" in the Burgtheater. There is a clue of sorts in the autograph. On its last page the composer confused the order of the instruments, mixing up the oboes and the violins, very untypical of Joseph Haydn, who jotted down, as if laughing at himself, the words "im schlaff geschrieben". This could indicate that he had to write out the work hurriedly, perhaps in addition to all his regular duties. (Daniel Heartz, "Leutgeb and the 1762 horn concertos of Joseph and Johann Michael Haydn", Mozart-Jahrbuch 1987/88, Kassel: Bärenreiter 1988, 59-64)

Haydn's note on the score actually reads "in schlaf geschrieben". The transcription "schlaff" that widely appears in the literature is a typical example of the old double-stroke f being mistaken for a double f. The origin of the (basically nonsensical) German surnames "Hoffmann" from the name "Hofmann" and "Graff" from "Graf" was caused by exactly this misunderstanding.

Even some experienced archivists have not yet understood that most 16th–18th-century double fs are actually single ones, because the upper horizontal line of the "f" was curved downward which makes it appear like a second vertical stroke. Bach's "höchstnöthiger Entwurff" – to give a very prominent example – is really an "Entwurf".

There is a second inscription on the first page of the score which was obviously not written by the composer. In the critical report of the concerto's 1984 edition of the Haydn-Institut Makoto Ohmiya and Sonja Gerlach write the following.

In her commentary to the facsimile edition, weighing on the probability of the concerto having been Haydn's gift for Leitgeb on the occasion of the baptism of his daughter, Ingrid Fuchs writes:

The signatures of the musicians Anton and Sebastian Hofmann on the wedding contract of the court musician Johann Klemp (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 1588/1793). These are all single fs.

Even some experienced archivists have not yet understood that most 16th–18th-century double fs are actually single ones, because the upper horizontal line of the "f" was curved downward which makes it appear like a second vertical stroke. Bach's "höchstnöthiger Entwurff" – to give a very prominent example – is really an "Entwurf".

The word "Hof" written with an apparent double-stroke single f (with the upper horizontal line bent downward) that is widely mistaken for a double f.

Samples of double-stroke single fs from a 1753 marriage entry in the records of the Schotten parish: it is "Graf", "Grafen von Kuefstein" and "wonhaft".

This clip from Daniel Gran's 1723 marriage entry reads "Hofmahlers" (Währing, Tom. 2, 29)

Another clip from the same document, reading "Hof und MundtKoch"

The name "Georg Graf" (from 1748)

"Francisca Dorferin" (1748)

"Rother Apfel" (from 1750)

Haydn's ironical note "in schlaf geschrieben" on top of the last page of the autograph of his horn concerto (A-Wgm)

There is a second inscription on the first page of the score which was obviously not written by the composer. In the critical report of the concerto's 1984 edition of the Haydn-Institut Makoto Ohmiya and Sonja Gerlach write the following.

Haydns Autograph enthält keinerlei Hinweis auf eine besondere Bestimmung. Doch gibt es auf der ersten Seite, von ungelenker Hand geschrieben, die rätselhafte Aufschrift "leigeb N[?] 6". Es wäre nicht undenkbar, daß das erste Wort einer Verstümmelung des Namens Leutgeb darstellt.

Haydn's autograph contains no reference to a specific assignment. But on the first page, written by a clumsy hand, there is a mysterious entry "leigeb N[?] 6". It would not be unthinkable that the first word is a garbling of the name Leutgeb.

Und noch ein ein weiterer beachtenswerter Hinweis auf den Empfänger bzw. Interpreten des Konzertes ist hier anzuführen: Auf der ersten Seite der autographen Partitur kann man am unteren Rand von etwas ungelenker Hand "leigeb n[ummer?] 6" lesen – möglicherweise eine Verballhornung des Namens Leutgeb, der häufig auch in der Fassung "Leitgeb" überliefert ist und in dieser Form der Angabe "leigeb" noch näher kommt.

There is yet another remarkable clue to be mentioned that points to the recipient, respectively the performer of the concerto: on the first page of the autograph score on the lower margin one can read the slightly clumsy entry "leigeb n[umber?] 6" – possibly a corruption of the name Leutgeb which is frequently also passed on as "Leitgeb" and in this spelling comes even closer to the entry "leigeb".

Fuchs's claim that the entry "leigeb" points to Joseph Leitgeb as recipient and owner of the autograph score is correct. The assumption that it is "possibly a corruption of the name Leutgeb", however, misses a fact that is quite obvious for somebody who is acquainted with Leitgeb's handwriting: the name on the first page of the score is Leitgeb's own autograph signature.

Joseph Leitgeb's signature on the first page of Haydn's horn concerto: "leigeb n[ummer] 6" (A-Wgm)

Leitgeb seems to have owned a whole collection of autograph scores of which Haydn's concerto was "nummer 6". When during the last decade of his life Leitgeb was hard pressed for cash, with the Austrian monarchy approaching the 1811 state bankruptcy, he (or his widow) was obviously forced to sell the valuable autograph to Archduke Rudolph from whom it came to the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde. Several documents from Leitgeb's hand prove unambiguously that he wrote the name on the score of the concerto. A document that bears Leitgeb's signature dating from before Mozart's death is the contract related to his second marriage in January 1786.

Joseph Leitgeb's and his best man Ignatz Dorner's seals and signatures on Leitgeb's 1786 marriage contract (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 5133/1811)

It is immediately obvious that spelling was not really Leitgeb's forte. The missing g in "breitiam" (Bräutigam, i.e. groom), which resembles the missing t in "leigeb", is especially telling. It is not even fully clear what the last word in the above signature is supposed to mean. If it means "leedig" (unmarried) it contradicts the date of the contract which was signed two days after the wedding.

Joseph Leitgeb's signature in the minutes of the Tonkünstler-Sozietät of 1 April 1791 (A-Wsa, Haydn-Verein, A2/1)

A better and much more significant example of Leitgeb's handwriting and spelling skills is the postscript to his will which he signed on 1 June 1801. For obvious reasons, the will proper was not written by the testator. Leitgeb's writing skills show that he was exactly the man who was able to sign his own name with a letter missing.

Leitgeb's autograph postscript on the last page of his will (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A10, 144/1811)

ich hab meina tochder ein schrif gemach vön meina / golden uhr die schrif ist for nula und nichtz/ anzusechen die sol mein Frau Ver Kaufen / und daß Gelt soln die trei Könda be Komen / fon Ernst daß sein armenarn – – – – / meine Kleitdung und wöß daß sol mein / son Fridarich leitgeb alß be Komen, aber / nicht aufa mal nur, wen meine Frau / wiel wen sie wiel ale Jahr oder ale / halbe Jahr. / daß ist mein lößtda / wile und meinung / Joseph leitgeb

[translation:]

I wrote a certificate for my daughter regarding my golden watch, this certificate should be regarded as null and void, my wife should sell it and the money should go to the three children of [my son] Ernst, those are poor fools. My clothes and linen should all go to my son Friedrich Leitgeb, but not all at once, only whenever my wife wants, every year or every half year. This is my last will and disposition. Joseph Leitgeb

Leitgeb's bizarre German spelling is actually not an exception, but rather the rule as far as the basic education of eighteenth-century musicians is concerned. Our modern day image of musicians as highly educated and well-read artists has little to do with orchestra musicians of Mozart's time, who, although ranking among the greatest virtuosi of their days, by no means were educated and highly cultured individuals. They much more resembled extremely skilled craftsmen, sometimes akin to savants, than what we nowadays consider musical artists. The general lack of education and the very limited writing skills of Viennese orchestra musicians, who in their level of education are comparable to excellent handymen, are the reason for the complete lack of contemporary reports and statements from a musician's perspective on Mozart's music.

Viennese orchestra musicians rarely left handwritten personal documents and Leitgeb was no exception. This guy was a one-track specialist of horn playing who certainly excelled in no other skill such as cheese making. Mozart's making fun of him may well have been related to Leitgeb's complete lack of extramusical education. It seems likely that Leitgeb also owned the autograph scores of other concertos he performed at the Burgtheater. The horn concerto he performed in Paris in 1770, which was claimed to be his own composition, might well have been Michael Haydn's lost work. After all, similar to Joseph Haydn's wife seven years earlier, Michael Haydn's wife also was the godmother of one of Leitgeb's children: Maria Magdalena Victoria Leitgeb, who was born on 23 December 1769, in Salzburg, was named after the "Hochfürstliche Concert=Maisterin und Hof=Cantatricin" Maria Magdalena Haydn, née Lipp.

The autograph signature of Leitgeb's colleague, the court hornist Jakob Eisen (1755–1796) (Schotten, Tom. 36, fol. 90)

Viennese orchestra musicians rarely left handwritten personal documents and Leitgeb was no exception. This guy was a one-track specialist of horn playing who certainly excelled in no other skill such as cheese making. Mozart's making fun of him may well have been related to Leitgeb's complete lack of extramusical education. It seems likely that Leitgeb also owned the autograph scores of other concertos he performed at the Burgtheater. The horn concerto he performed in Paris in 1770, which was claimed to be his own composition, might well have been Michael Haydn's lost work. After all, similar to Joseph Haydn's wife seven years earlier, Michael Haydn's wife also was the godmother of one of Leitgeb's children: Maria Magdalena Victoria Leitgeb, who was born on 23 December 1769, in Salzburg, was named after the "Hochfürstliche Concert=Maisterin und Hof=Cantatricin" Maria Magdalena Haydn, née Lipp.

The entry concerning the baptism of Maria Magdalena Victoria Leitgeb on 23 December 1769 in the Salzburg Cathedral (Archiv der Erzdiözese Salzburg, Dompfarre 9/2, 265)

Dieß et Hora Partus et Baptismi. 23. [Decembris] h:[ora] 3: pomer:[idiana] nata, et h: 6 vesp:[era] Baptizata e[st]

Proles. Maria Magdalena Victoria fil:[ia] leg:[itima]

Parentes. D:[ominus] Josephus Leitgeb Hof=Waldhornist : et Maria Barbara Plazerianin coniuges.

Patrini. Anna Maria Magdalena Heÿdin Hochf[ürstliche] Concert=Maisterin und Hof=Cantatricin.

Minister. A:[ltus] R:[everendus] D:[ominus] Wolfgangus Rizenberger Cooperator.

Joseph Leitgeb's seal on the envelope of his will (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A10, 144/1811)

© Dr. Michael Lorenz 2013.

Updated: 27 September 2023

Research for this article was generously funded by Dr. Lucia Schuger (University of Chicago).

Thank you for this interesting excursion into the bye-ways of a horn player. As a Vienna horn player myself, when I am in Vienna next week I shall look out for the locations you mention.

ReplyDeleteI look forward to your more detailed publication.

This is so interesting. I hope you will publish it to a wider audience. I will post a link of this to the horn people's page on Facebook.

ReplyDeleteEinfach FANTASTISCH !!!!

ReplyDeleteVergellts Gott

Whelden Merritt

Extremely interesting! I always regretted the lack of information about one of the most important hornplayers in history, since the world of hornplayers owe Mozarts wonderful concertos to this lifelong friend of him. So all hornplayers woldwide are eager to read more about the results of your scrutinizing research.

ReplyDeleteThank you so much!

Albert Heitzinger

Thank you, Dr. L., for your greatly informative post. When one is seeking truth in these matters, it is a hard thing to find. You strip away the errors of the centuries!

ReplyDeleteGurn

Dear Michael,

ReplyDeleteThanks for the info. It's great to see you unravel falsehoods that have taken hold over the centuries.

This is a very interesting and informative article! I actually used some of the valuable information it contains for my class. Are you aware of this article? This is aslo quite interesting. http://www.academia.edu/3217350/The_Doubtful_Authenticity_of_Mozart_s_Horn_Concerto_K_412

ReplyDeleteMaria Fotia

Thank you for sharing your research. This was great and useful.

ReplyDeleteFascinating! You show that it is necessary (a) to see the archical evidence, (bI to read it (complex letters f and all), (c) to understand it with all its conventions.

ReplyDeleteDear Dr. Lorenz, congratulations for your work. I am myself searching after Leutgeb the Ghost. If you have anything about his horn, the very instrument he played, please email me. nico.roudier@gmail.com Thank you very much

ReplyDeleteDear Dr Lorenz, Thank you for your splendid work on Leitgeb. I wondered if you could throw any light on for whom the Haydn Zittau concerto was written. Perhaps Leitgeb played it at the Burgtheater but it seems to me that it was written for a cor basse player, which Leitgeb was not. Do you think he wrote it in Grosswardein and gave it to Leitgeb when he moved to Salzburg? The style seems to indicate early 1760s. I am playing the concerto quite soon so my curiosity is piqued. Incidentally my reconstructions of the Mozart 1781 & 1791 horn concertos have been recorded by Roger Montgomery with the OAE and by Pip Eastop and the Hanover Band. I am indebted to your research for providing the programme notes! Yours, Dr Stephen Roberts

ReplyDeleteAs far as I can see, there's no proof that the Zittau concerto is a work of Haydn.

ReplyDelete